British Abolitionist Movement

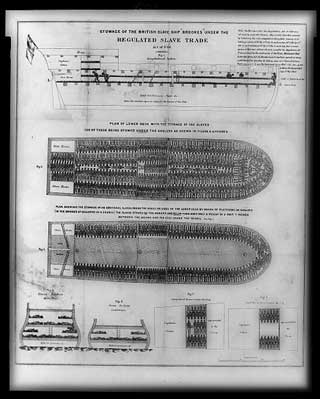

In an age before photography, social reformers in Great Britain knew that in order to end the slave trade they would have to expose the slave trade. They used first-hand testimonies from people who conveyed the deplorable conditions of the slave ships. They showed chains and other equipment used to abuse Africans. In 1788, they began using one of their most powerful tools: a drawing of the inside of the slave ship “Brookes.”

In an age before photography, social reformers in Great Britain knew that in order to end the slave trade they would have to expose the slave trade. They used first-hand testimonies from people who conveyed the deplorable conditions of the slave ships. They showed chains and other equipment used to abuse Africans. In 1788, they began using one of their most powerful tools: a drawing of the inside of the slave ship “Brookes.”

Adam Hochschild, in his book “Bury the Chains,” provides an in-depth study of the history of the abolitionist movement and the key players of the cause. He ends his book with this insightful passage:

To the British abolitionists, the challenge of ending slavery in a world that considered it fully normal was as daunting as it seems today when we consider challenging the entrenched wrongs of our own age: the vast gap between rich and poor nations, the relentless spread of nuclear weapons, the multiple assaults on the earth, air, and water that must support future generations, the habit of war. None of these problems will be solved overnight, or perhaps even in the fifty years it took to end British slavery. But they will not be solved at all unless people see them as both outrageous and solvable, just as slavery was felt to be by the twelve men who gathered in James Phillips’s printing shop in George Yard on May 22, 1787.

All of the twelve were deeply religious, and the twenty-seven-year-old Clarkson wore black clerical garb. But they also shared a newer kind of faith. They believed that because human beings had a capacity to care about the suffering of others, exposing the truth would move people to action. ‘We are clearly of opinion,’ Granville Sharp wrote to a friend later that year [1787], ‘that the nature of the slave-trade needs only to be known to be detested.’ Clarkson, writing of this ‘enormous evil,’ said that he ‘was sure that it was only necessary for the inhabitants of this favoured island to know it, to feel a just indignation against it.’ It was this faith that led him to buy handcuffs, shackles, and thumbscrews to display to the people he met on his travels. And that led him to mount his horse again and again to scour the country for witnesses who could tell Parliament what life was like on the slave ships and the plantations. The riveting parade of firsthand testimony he and his colleagues put together in the Abstract of the Evidence and countless other documents is one of the first great flowerings of a very modern belief: that the way to stir men and women to action is not by biblical argument, but through vivid, unforgettable description of acts of great injustice done to their fellow human beings. The abolitionists placed their hope not in sacred texts, but in human empathy.2

Back to Historical Social Reform

- Adam Hochschild, Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006), 155-6.

- Hochschild, 365-6.