Do the Pre-Born Unjustly Use Another’s Body?

Philosophy professor, Dr. Andrew Sneddon, of the University of Ottawa, once argued that even if the pre-born are full members of the moral community like adults, abortion is permissible because pregnancy involves an extraordinary act on behalf of the mother. This was the analogy he used to make his case:

Suppose that you are in need of a kidney transplant in order to survive, and that your mother is the only person in the world who is a physical match, meaning that she is the only person who can provide you with a kidney and hence preserve your life. Do you have a right to your mother’s kidney?1

The professor said it would be nice to provide one’s kidney or uterus, but a woman shouldn’t be forced to. In other words, he indicated that just because one may do it, it doesn’t mean one must. He explained that the kidney case is analogous to pregnancy in the following ways:

- It concerns two persons who stand in the relation of mother and child.

- Both are, uncontroversially [sic], full members of the moral community, with all of the rights that come with such membership.

- One person (the child) requires the other person’s body (the mother’s) to survive.2

The professor then described his central point as follows:

In the kidney case, my right to life and my need for my mother’s body to survive do not deliver any right whatsoever to her body, let alone a right that trumps her rights to control her body. The same goes for pregnancy.3

If that is true about the kidney, does it follow that it is true about the uterus?

While many things could be said in response to the professor’s claim, at the heart of our reply needs to be this question: What is the nature and purpose of the kidney versus the nature and purpose of the uterus? The answer tells us why one is not obligated to give her child her kidney, but is obligated to “give” her child her uterus.

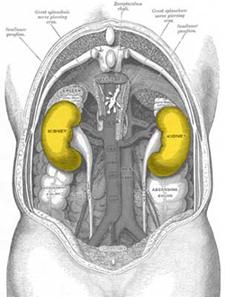

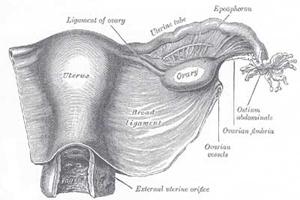

Once one looks at the function of the kidneys and the uterus, it is quite clear why the professor’s analogy does not have merit. The kidneys exist for the health and proper functioning of the body in whom they reside. In contrast, each month the uterus gets ready for someone else’s body.

Kidneys exist in a body, for that body. The uterus exists around a body (the pre-born’s), for that body. The fact that a woman can live without her uterus but a fetus cannot, illustrates that the uterus exists more for the pre-born child than for the mother.

Furthermore, mothers (and fathers) have a responsibility to their offspring that they don’t have to strangers.4 And while that responsibility doesn’t obligate them to do extraordinary things such as trips to Disneyland or donating kidneys, it does obligate them to do ordinary things, such as feeding, clothing, and sheltering one’s offspring. To do otherwise is parental neglect.

In fact, western countries make it illegal for parents to neglect their children. Parents have been convicted and jailed for “not providing the necessities of life” when they chose to not provide their children essential care.5

Therefore, maintaining pregnancy is simply doing for the pre-born what parents must do for the born—provide the shelter and nourishment a child needs. It is what is required in the normal course of the reproduction of our species.

Furthermore, abortion cannot be compared with refusing to donate one’s kidney because with abortion, the pre-born are directly and intentionally killed in the environment made for them. In contrast, the kidney-disease patient dies directly as a result of the kidney disease—not because of the choice of another person. As a physician once pointed out, “In the renal analogy if nothing is done, one person dies. In the pregnancy case, if nothing is done, no one dies.” The pre-born, as members of the human family, must not then be denied the environment that regularly waits in great expectation for them.

Fundamentally, the issue in responding to the kidney analogy is to examine the nature of the uterus.6 This perspective stumped the professor. Shortly after the debate where the professor articulated these views, an attendee reported, “The professor told his class that week that the argument that the womb was created for the child was literally keeping him up all night!”

And so, the professor’s kidney comparison can only be truly analogous with abortion if, once denying a kidney to her child, the mother would dismember, decapitate, and disembowel him too.

See also

| Previous: How We Value Humans | Next: Legal Issues |

- Abortion debate between Dr. Andrew Sneddon and Ms. Stephanie Gray, held at the University of Ottawa, February 27, 2009.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- In chapter 7 of Francis Beckwith’s book, Politically Correct Death: Answering Arguments for Abortion Rights (1993), it extensively covers arguments such as this when refuting an analogy similar to the professor’s. The points Beckwith makes are in response to an analogy proposed by abortion advocate Judith Jarvis Thomson, known as “unplugging the violinist” and articulated in her paper, “A Defense of Abortion.”

- Parents not Guilty of Manslaughter in Methadone Death, CTV News, available online here, accessed August 4, 2010.

- It should be noted that this perspective about the nature of the uterus does not preclude removing a cancerous uterus of a pregnant woman should its removal be required for the preservation of her life. The uterus is indeed a part of her body, not the pre-born’s (although it exists for the pre-born). Appealing to the Principles of Integrity and Totality, the removal of such a uterus would be warranted as its sacrifice is required for her very survival. Furthermore, in doing such a procedure prior to viability, the death of the pre-born child would be a foreseen but unintended effect of doing a good action, which is the removal of a pathological organ (applying the Principle of Double Effect here).